How to identify the best land to produce silage

It’s not a politically correct view anymore, but the evidence is undeniable, all things are not equal. Be it cows, tractors or fields, there will be differences between the performance of “the best” and the “also ran’s”. Every farmer knows this, but today its very dangerous to suggest someone isn’t very good at something unless they are a Premiership footballer or politician. And while a farm manager might know very well which cows are the high fliers, it’s becoming less likely that they have the same finger on the pulse when it comes to the land league table. In the unstoppable march into the future, have we lost some of these measures of performance?

Have we lost something in the move to the future of forage farming?

I suspect we might have because today there are more and more cows who spend most of their productive days eating silage rather than grass sward. This change has had numerous (undeniable) benefits but there is also one key disadvantage when it comes to forage production management. Back in the day, the herd at grass was a constant barometer of the sward quality and quantity. As soon as the girls moved to new pasture, the dipstick in the bulk tank or the flow meters in the parlour would give you an immediate measure of the forage value. But for those housing cows 365 or feeding bacteria in an AD tank, how do you know which ground is pulling its weight and which fields need some TLC?

Getting out and about a bit more often.

A wise sage once quoted that a healthy farmer should get:

off the farm once a day

get out of the village once a week

out of the county once and month

and out of the country once a year

In these days of enhanced awareness of mental health, I think this is probably sound advice and I am not going to detract from this list. But I am going to add something else to it, I think a healthy farmer with a healthy farm needs to get out of the yard and on to the land at least once a week too.

Getting out into the fields is not only good for your mental health it’s vital for the health of the business because this is where the lifeblood of the business comes from. Some dairy farmers can become fixated by the cow; and as long as the silage keeps coming and the slurry keeps disappearing then the land is doing its thing isn’t it? Well maybe but maybe not, as stated above, not all fields are equal.

Grazing cows will soon tell you which fields are producing great forage and which ones are not. But how do you know this when the forage all ends up in the same silage clamp?

Running an AD plant, the manager can become even more disconnected from the land. The forage feed stock is often produced on contract so the plant managers have no real rights of access to the land that produces the silage. This means that you are managing a plant with one hand tied behind your back because you have to take a product you’ve had no control over and try to make gas from it.

For the AD plant and the fully housed dairy herd, the vast majority of the feed value comes from silage. The silage you use is coming from many different fields some good, some great and some below par.

How can you identify good silage fields from those that need to be improved?

Getting out and about, and down on your hands and knees, you can get a feeling for the volume and quality of the crop. Feed back from the forage team will give you some more data but it’s hard to put any hard and fast numbers to this without putting every trailer over the weigh-bridge. To do that accurately, you are going to need to do some analysis, soil analysis, fresh crop analysis and silage analysis. And chances are you are more likely than not to use an agronomist to do this for you.

Using a NIR monitor to grow better silage

As an alternative to sending off forage for analysis, the manufactures will tell you that an on harvester NIR sensor can do all this for you. The claims sound great but just how accurate are these boxes and can you really trust them? There are some dissenting voices that will tell you the lab tests give very different results to the over inflated results from the chopper print out. That can be for many reasons including the delay in analysing at the lab compared to in the field. But don’t begin to think that NIR (Near Infer Red) sensors are an inferior solution because the labs all use this technology too. The results from any NIR sensor are only as good as the calibration data that the software uses. Laboratories that are part of the FAA (Forage Analysis Assurance) group all use a constantly updated collaborative calibration curve that makes their analysis results consistently accurate.

A poorly calibrated on-harvester sensor might not be as “accurate” as a lab test but its readings are completely accurate. It is just that the data is not corrected to the calibration data. The data from the harvester will still be relevant because the readings it takes are always consistent. So if the harvester tells you one block of land has produced silage that’s 12.5ME and the next block is 11.0ME, then the actual figures might not be “accurate” but the difference between them will be. The first block is significantly out performing the second block, by over 10%.

EvoNIR from Dynamic Generale

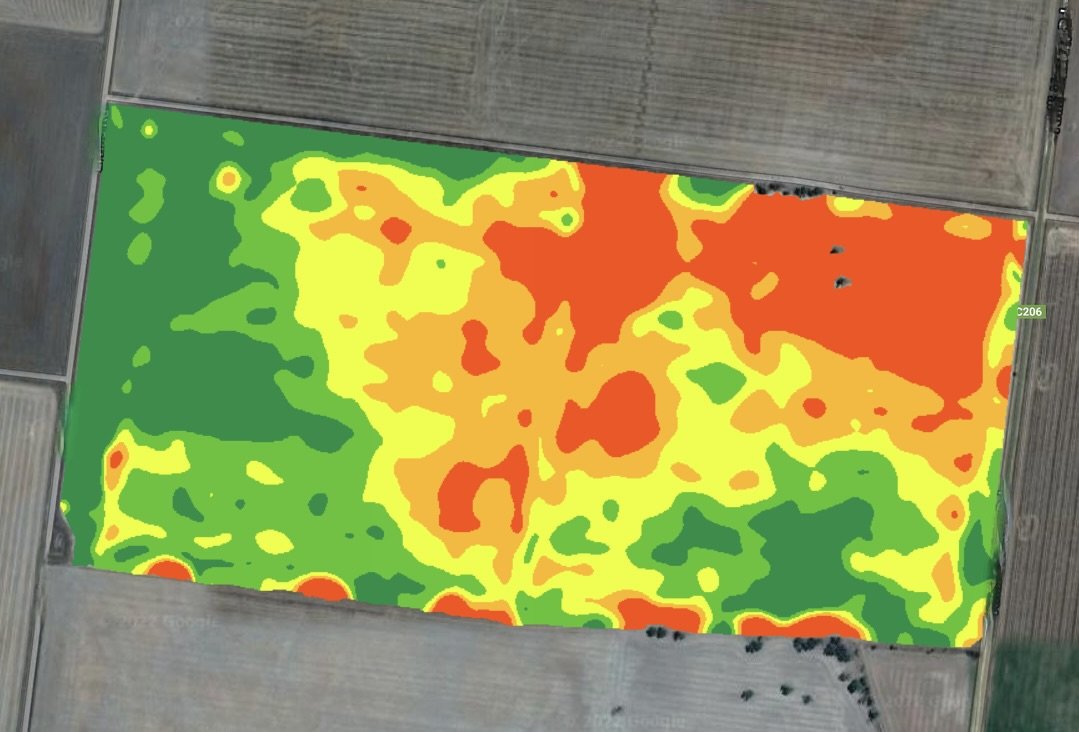

The data you get from this technology can also give you yield and quality maps for each field so you can see what areas are under performing. This information means you can target improvements to specific areas of land rather than whole fields.

Can NIR replace the agronomist?

In terms of data collection, the NIR monitor is unparalleled; no agronomist could ever sample at the rate a harvester can. But the data collection is only part of the job; this data needs to be analysed and someone needs to decide what to actually do to make the next harvest better.

What the agronomist working with data from the NIR sensor can do, is make you aware of exactly what each field is doing and how you can improve it – in a far, far, more detailed way than the dipstick in the bulk tank ever could.

If you want to discuss how to make better silage or want to discuss any of the other aspects of silage making covered in this series – contact Jeremy Nash at Jeremy@silageconsultant.co.uk